The first part in this series on Reflection in C++ gave a high level overview of many of the possibilities open to you when adding reflection to your games. In this second part I’m going to go into details and cover the system used to aid the rendering engine in Splinter Cell: Conviction (SC5).

The motivation for the development of the SC5 engine was a clean break from the past. We were working with a very, very large code base that used Unreal 2.5 with many years of modifications and rewrites. While immensely stable, visually very good looking and a code base you could bet a few million dollars on, it slowed the development of new techniques required to push the SC franchise onto the next generation of consoles (the XBox 360, circa 2005).

Compile times were painfully slow, link times were in the order of minutes and it suffered from the classic Unreal issue of requiring huge rebuilds whenever you changed a .uc script file (used to define your interfaces to the editor, among other things – partially solved in Unreal 3). There were many levels of pipeline and engine indirection added to ship titles that were slowing down the iteration and development of new techniques, simultaneously contributing to a lack of runtime performance on the target platform. After a couple of months, we were at a few seconds for compile/link on the PC, sub-1 second single file iteration times, vastly simpler/faster import pipelines, multi-threaded performance that was orders of magnitude faster on the Xbox 360 than the old engine, the ability to live edit C++ rendering code and no compile dependency on Unreal.

As a result we lost a few key technologies along the way that would have helped immensely, such as the ability to carve indoor space up using BSP volumes. We also ended up recreating some already existing features such as light association control and skeletal attachments. But the full story is something for another day and Stephen Hill’s fantastic GDC 2010 piece on the development of some of the rendering technologies can give a bit more insight (Rendering with Conviction).

This post will cover just the reflection API developed to replace Unreal’s object model. The implementation was very simple, written in a couple of days, constrained to a single cpp/h file pair and slowly grew as the needs of the engine evolved. It also helped us develop the new engine while the old engine was still active, supporting 50 odd developers and keeping game progress undisturbed. It is my hope that I can demonstrate how simple (and sometimes naive) solutions can help ship great games, as long as you’re willing to rub shoulders with some pretty big limitations.

An example of such a system is Reflectabit, written a few years ago in my spare time. It’s unfinished but contains enough to serve as a tutorial of sorts. This post is from memory as I don’t have the code to hand anymore.

The Type ID

The first task in any reflection API is defining what a “type id” is: how can you reference types in code? For SC5 we needed a type ID that:

- Could reference built-in types (int, char, etc) as well as custom class types.

- Was unique for each type.

- Was persistent between program invocations.

- Could be used for serialisation.

The simplest of solutions is to use an enum:

enum TypeID { TYPE_INT, TYPE_CHAR, TYPE_MYTYPE, // ... }; |

Each time you add a new type, you add it to the end of the enum. This needs a means of mapping a C++ type to its enum:

// Each reflected type must specialise this template <typename TYPE> inline TypeID GetTypeID() { // Compile-time assert: Type not implemented (avoiding a return value is enough, really) }; // Specialisation examples inline template <> TypeID GetTypeID<int>() { return TYPE_INT; } inline template <> TypeID GetTypeID<char>() { return TYPE_CHAR; } inline template <> TypeID GetTypeID<MyType>() { return TYPE_MYTYPE; } |

This is not particularly extensible or maintainable in larger projects: if you’re working on a changelist that adds a new type and you are using it for serialisation, any incoming changes from members of your own team have the potential to clobber all your data and make the act of submission a chore that is potentially very dangerous. Type IDs will accrue over time and you must ensure that types are added at the end of the list. It’s not suitable for a reflection API that ships as part of a 3rd party library that expects its client code to add its own type, although there are many examples of such systems in decades old code (WM_APP).

One good benefit of this method is that you can immediately see the type name in a debugger when inspecting values of type TypeID. However, you can’t see them at runtime unless you add a means of also mapping the enum value to a string. Of course, there are ways to do this, for example:

// TypeIDs.inc: // List all Type IDs TYPEID(TYPE_INT) TYPEID(TYPE_CHAR) TYPEID(TYPE_MYTYPE) // TypeIDs.h: // Build the enum table #define TYPEID(type) type, enum TypeID { #include "TypeIDs.inc" }; // Use the pre-processor "stringiser" operator to specify the name of each name #undef TYPEID #define TYPEID(type) #type, const char* g_TypeNames = { #include "TypeIDs.inc" }; |

This is a well-used technique in many shipping C/C++ products where its variants have been branded X Macros. At this point it’s all getting a bit messy/overkill; we ruled it out on SC5 without much thought as there was a much simpler solution:

// Each reflected type must specialise this template <typename TYPE> const char* GetTypeName() { // Compile-time assert: Type not implemented } // Specialisation examples inline template <> const char* GetTypeName<int>() { return "int"; } inline template <> const char* GetTypeName<char>() { return "char"; } inline template <> const char* GetTypeName<MyType>() { return "MyType"; } template <typename TYPE> u32 GetTypeID() { // Calculates the string hash once and then caches it for further use static int type_id = CalcStringHash(GetTypeName<TYPE>()); return type_id; }; |

As long as your hash function is good this is a great way of defining your type ID support:

- Practically, you are guaranteed unique, persistent IDs as long as your typenames are unique (you can prefix namespaces if you like).

- Types can be added in isolation; all you need to do is implement your GetTypeName alongside its type in a header file.

- The type names are readily available in the debugger and are part of your executable.

The choice of hash function is important but don’t overthink the issue. SC5 used CityHash). Whatever you choose, collision visibility is essential as collisions can cause very subtle data integrity issues.

Before going any further, a small review of some other methods of generating a type ID may be of interest.

The first is to use C++ RTTI to replace GetTypeName:

template <typename TYPE> const char* GetTypeName() { return typeid(TYPE).name(); } |

Note that this is not using any runtime aspects of C++ RTTI support beyond calling a function in the type_info object returned, which needs to store its information somewhere in memory. Technically this means you should not be penalised for its use at runtime (it doesn’t alter the size of any of your objects) but I’ve only tested this on MSVC platforms. This is a remarkably simple solution that doesn’t require you to specialise GetTypeName.

One issue you can encounter is that RTTI is a very loosely standardised feature of C++ and different platforms may return different names for each type. I believe GCC mangles the result in some way, although none of these issues are insurmountable. Curiously, if you disable RTTI in an MSVC project, typeid still works, demonstrating the theory of no runtime penalty. However, other compilers such as GCC fail to compile.

Another non-standard side-step involves the use of the pre-defined __FUNCTION__ (C99) macro or whatever equivalent your compiler most likely has these days:

template <typename TYPE> const char* GetTypeName() { // GCC's equivalent is __PRETTY_FUNCTION__ return __FUNCSIG__; } |

This is MSVC-specific but the output is:

const char *__cdecl GetTypeName<struct MyType>(void) |

An important realisation is that this string is unique if your type name is unique so you don’t really need to change it. If that bothers you, however, you can do a quick parse of the string and cache it locally in a static char buffer, or similar.

A final method I’d like to cover is one which has caught me out in a moment of error:

#define GetTypeName(type) #type |

It’s alluringly simple and works, except for one fatal flaw; it can’t be used within templates:

template <typename TYPE> void SomeUtilFunction() { // Returns the string "TYPE" const char* type_name = GetTypeName(TYPE); } |

Types in Memory

The next step is in defining how types are represented in memory, their dynamic retrieval and how they can be used to create objects of that type. This involved a few structures:

// Used for both type names and object names struct Name { unsigned int hash; const char* text; }; // Function types for the constructor and destructor of registered types typedef void (*ConstructObjectFunc)(void*); typedef void (*DestructObjectFunc)(void*); // The basic type representation struct Type { // Parent type database class TypeDB* type_db; // Scoped C++ name of the type Name name; // Pointers to the constructor and destructor functions ConstructObjectFunc constructor; DestructObjectFunc destructor; // Result of sizeof(type) operation size_t size; }; // A big registry of all types in the game with methods to manipulate them class TypeDB { public: // Example methods; implementations discussed later Type& CreateType(Name name); Type* GetType(Name name); private: typedef std::map<Name, Type*> TypeMap; TypeMap m_Types; }; |

We didn’t use the STL to define our types; I’m using it above to demonstrate intent.

The Name type always stored both the null-terminated string pointer and hash of that string. Type names were always present, stored in a read-only segment of memory when the compiler encounters any calls to GetTypeName. Object names were never stored in memory. Instead, they were stored in a MySQL database which was queried by a Visual Studio debugger plugin whenever it wanted to display a name in the watch window. This was a great way of always having object names present in console builds without consuming runtime memory, even in our most final release builds.

Types are created dynamically as part of game initialisation and a simple implementation of CreateType would be:

template <typename TYPE> Type& CreateType(Name name) { // Only allocate the type once (GetType will call CreateType if the type doesn't exist) Type* type = 0; TypeMap::iterator type_i = m_Types.find(name); if (type_i == m_Types.end()) { type = new Type; m_Types = type; } else { type = i->second; } // Apply type properties type->type_db = this; type->name = name; type->size = sizeof(TYPE); return *type; } // Example registration on initialisation TypeDB db; db.CreateType<MyType>(); |

This gives enough information to be able to allocate enough space for objects of a given type but a means of constructing/destructing that object has yet to be defined. In C++ you can’t create function pointers to the constructor or destructor (see C++98 12.1 for more info) but given a memory address, they can be called:

template <typename TYPE> void ConstructObject(void* object) { // Use placement new to call the constructor new (object) TYPE; } template <typename TYPE> void DestructObject(void* object) { // Explicit call of the destructor ((TYPE*)object)->TYPE::~TYPE(); } |

This now allows CreateType to fully define Type:

template <typename TYPE> Type* CreateType(NAME name) { // ... alloc type ... // Apply type properties type->size = sizeof(TYPE); type->constructor = ConstructObject<TYPE>; type->destructor = DestructObject<TYPE>; return *type; } |

This is enough information to dynamically create objects of a given type, which will be discussed later. Finally, the default type database needs to register all C++ types that were supported in its constructor:

TypeDB::TypeDB() { CreateType<char>(); CreateType<short>(); CreateType<int>(); CreateType<float>(); // ... and so on ... } |

Fields

Each type contains an array of fields that describe it – called a PropertyInfo in SC5. We needed the field descriptions to be able to serialise and inspect any object, requiring the following structure:

struct Field { // C++ name of the field, unscoped Name name; // Name of the field type name and a pointer to its type Name type_name; Type* type; // Is this a pointer field? Note that this becomes a flag later on... bool is_pointer; // Offset of this field within the type size_t offset; }; |

Only value and pointer field types were supported and the const-ness was irrelevant.

We wanted a means of automatically generating the properties of a field to avoid manually-specified registration errors. A typical structure with the desired registration mechanism could look like this:

struct MyType { int x; float y; char z; OtherType other; OtherType* other_ptr; }; Field fields = { Field("x", &MyType::x), Field("y", &MyType::y), Field("z", &MyType::z), Field("other", &MyType::other), Field("other_ptr", &MyType::other_ptr) }; // Create the type and specify its fields TypeDB db; db.CreateType<MyType>().Fields(fields); |

Of course, while the properties of a field are automatically deduced, the specification of what fields comprise a type is manual. This caused a few errors along the way on our small team and it was thought that the effort involved trying to minimise this wasn’t a priority.

Note that the field for OtherType is created before OtherType is potentially created. To offset the need to register types in any specific order, any calls to GetType would allocate the type if it didn’t already exist. Subsequent calls to CreateType would retrieve the allocated copy and describe it.

Note also that the field name is manually specified, which is another potential source of user error. Instead, we could have used the pre-processor stringising operator to ensure it was in sync. Again, this wasn’t considered important and at the time and I didn’t fancy adding extra layers with pre-processor macros. I did start playing around this a couple of years ago and some investigative results can be found in Reflectabit’s serialisation tests. I still prefer the manual solution, however.

Implementing the Field constructor requires answering three questions at compile-time:

- What type is the field?

- Is it a pointer?

- What is the field offset?

This required two utility functions that used partial template specialisation on the type qualifiers to identify a pointer and also strip a pointer from the type:

// Does a type specification contain a pointer? template <typename TYPE> struct IsPointer { static bool val = false; }; // Specialise for yes template <typename TYPE> struct IsPointer<TYPE*> { static bool val = true; }; // Exactly the same, except the result is the type without the pointer template <typename TYPE> struct StripPointer { typedef TYPE Type; }; // Specialise for yes template <typename TYPE> struct StripPointer<TYPE*> { typedef TYPE Type; }; |

It also required the use of the offsetof macro, making the assumption that we never use virtual or multiple inheritance (we didn’t). With these tools, the Field constructor is quite simple:

struct Field { template <typename OBJECT_TYPE, typename FIELD_TYPE> Field(Name name, FIELD_TYPE OBJECT_TYPE::*field) : name(name) // Store the type name as we don't have an owning type database yet , type_name(GetTypeName< StripPointer<FIELD_TYPE>::Type >()) , type(0) , is_pointer(IsPointer<FIELD_TYPE>::val) , offset(offsetof(OBJECT_TYPE, *field)) { } }; |

The Fields method in Type uses the Named Parameter Idiom to assign a field list to a type. This technique is used pretty frequently to make registration as friendly as possible. Fields is implemented using templates to figure out the size of the C array:

struct Type { template <int SIZE> Type& Fields(Field (&init_fields)) { for (int i = 0; i < SIZE; i++) { Field f = init_fields; // Assign the type pointer using the parent type database and add to the type's field list f.type = type_db->GetType(f.type_name); fields.push_back(f); } return *type; } // New vector of fields for this type std::vector<Field> fields; }; |

Inheritance

All registered types could only have one base class and fields declared within that type only existed in the fields array of that type (i.e. the fields within an inheritance hierarchy weren’t merged). Registering a base class was done with another method in Type:

struct Type { template <typename TYPE> Type& Base() { base = type_db->GetType(GetTypeName<TYPE>()); } Type* base_type; }; // Example registration TypeDB db; db.CreateType<SomeType>().Base<ItsBaseType>(); |

Enumerations

Similar to what was described in part 1 of this series, enumeration constants were simply a name/value pair:

struct EnumConst { EnumConst(Name name, int value) : name(name), value(value) { } Name name; int value; }; |

However, in an attempt to keep the API simple and avoid any inheritance trees, there was no enumeration type. Instead, each type had a list of enum constants which would be empty if the type was not an enumeration:

struct Type { template <int SIZE> Type& EnumConstants(EnumConst (&input_enum_consts)) { for (int i = 0; i < SIZE; i++) enum_constants.push_back(input_enum_consts); } // Only used if the type is an enum type std::vector<EnumConst> enum_constants; }; |

Registering of enumeration constants then became as easy as:

enum TestEnumType { VAL_A, VAL_B, VAL_C }; // Collate the enum constants EnumConst enum_consts = { EnumConst("VAL_A", VAL_A), EnumConst("VAL_B", VAL_B), EnumConst("VAL_C", VAL_C), }; // Create the enum type TypeDB db; db.CreateType<TestEnumType>().EnumConstants(enum_consts); |

Again, this relies upon manual registration of any enumeration constants you have and can be error-prone if you forget to add a constant or incorrectly name it. I can’t recall this causing us any issues but the potential for making mistakes was there. We were careful and determined that going any further would not be a good investment of our time.

Attributes

Attribute systems can get pretty complicated but we wanted something quick and simple that could be improved at a later date if necessary. We pretty much knew from the outset what attributes we would require so each field was extended to contain:

struct Field { Field& Flags(unsigned int f) { flags = f; return *this; } Field& Desc(const char* desc) { description = desc; return *this; } Field& Group(const char* g) { group = g; return *this; } // An ORing of boolean attributes and a version number (explained later) unsigned int flags; // An optional property description for editors Name description; // An optional user interface grouping node name for editors Name group; }; |

These are entirely hard-coded attributes that the reflection system defines. There are only two string attributes: description and group, that are used for user interface population. If you’re defining a material type then you can group its properties into (for example) “Textures” and “Lighting”.

The rest of the attributes were boolean flags, merged into the single flags field. Some examples are:

enum Flags { // Is this field a pointer type? (replacing the is_pointer bool in Field) F_Pointer = 0x01, // Is this a transient field, ignored during serialisation? F_Transient = 0x02, // Is this a network transient field, ignored during network serialisation? // A good example for this use-case is a texture type which contains a description // and its data. For disk serialisation you want to save everything, for network // serialisation you don't really want to send over all the texture data. F_NetworkTransient = 0x04, // Can this field be edited by tools? F_ReadOnly = 0x08, // Is this a simple type that can be serialised in terms of a memcpy? // Examples include int, float, any vector types or larger types that you're not // worried about versioning. F_SimpleType = 0x10, // Set if the field owns the memory it points to. // Any loading code must allocate it before populating it with data. F_OwningPointer = 0x20 }; |

As evident, you could only add new boolean attributes if there were flag bits left and adding attributes with more complexity required extending Field. Perfect for our use-case but not ideal for a more general system.

Containers

Our container support was very primitive, similar to the container support in Reflectabit but lacking its completeness. The basic premise was to use an interface pointer to an underlying container wrapper, like so:

struct IContainer { virtual int GetCount() = 0; virtual void* GetValue(void* container, int index) = 0; // ...etc... }; // An example container implementation for std::vector template <typename TYPE> struct VectorContainer { int GetCount() { return ((std::vector<TYPE>*)container)->size(); } void* GetValue(void* container, int index) { return &((std::vector<TYPE>*)container)->at(index); } }; struct Field { // The first constructor, specified above Field(// ... // An overload for std::vector container fields template <typename OBJECT_TYPE, typename FIELD_TYPE> Field(Name name, std::vector<FIELD_TYPE> OBJECT_TYPE::*field) : name(name) , type_name(GetTypeName< StripPointer<FIELD_TYPE>::Type >()) , type(0) , is_pointer(IsPointer<FIELD_TYPE>::val) , offset(offsetof(OBJECT_TYPE, *field)) { // Allocate the implementation container = new VectorContainer<TYPE>(); } IContainer* container; }; |

There is more information on the technique in part 1 of this series. Again, we didn’t use any STL code, opting for our own custom containers, so the above is just an example to highlight how it was achieved. For each field container type, the compiler will generate all of the necessary code to access/mutate the containers which are controlled through the container interface. It’s not ideal in terms of generated code size but it’s simple and it works well enough.

Working with objects

We had the luxury of not having to create a controlling object model as Unreal’s package system was already doing a good enough job. As a result, all of our objects were anonymously contained by an equivalent UObject and we merely had a resource database that mapped object names to their instances:

// The base object type for root-serialisable objects struct Object { // Called after post-load or any UI modified properties, allowing the internal // representation to update itself virtual void OnChanged() = 0; Name name; Type* type; }; class ResourceDB { public: // Fundamental object management methods Object* CreateObject(Name name, Type* type); void DestroyObject(Object* object); // Helper for retrieving the type and applying the appropriate cast template <typename TYPE> TYPE* CreateObject(Name name) { return (TYPE*)CreateObject(name, m_TypeDB->GetType(GetTypeName<TYPE>())); } Object* GetObject(Name name); private: TypeDB* m_TypeDB; // Map of all objects typedef std::map<Name, Object*> ObjectMap; ObjectMap m_Objects; }; |

CreateObject was used everywhere: from serialisation to networked object creation. It used the description of whatever type was being created to safely construct whatever you needed:

Object* ResourceDB::CreateObject(Name name, Type* type) { // Allocate enough space for the object and call its constructor Object* object = (Object*)malloc(type->size); type->constructor(object); // Assign its properties object->name = name; object->type = type; return object; } |

This was paired with DestroyObject and both replaced typical new/delete use:

void ResourceDB::DestroyObject(Object* object) { // Call destructor and release memory object->type->destructor(object); free(object); } |

With a few helpers, you already can do some pretty funky things not normally possible with C++:

struct Field { // Helper to get a pointer to the field within an object void* GetPtr(void* object) { return (char*)object + offset; } }; struct Type { // A simple linear search looking for a field by name Field* GetField(const char* name) { for (size_t i = 0; i < fields.size(); i++) { // This is just a hash comparison if (Name(name) == fields->name) return fields; } // Recurse up through base type if (base_type) return base_type->GetField(name); return 0; } }; // Create an object using its type name TypeDB db; ResourceDB rdb; MyType* mt = rdb.CreateObject("objectname", db.GetType("MyType")); // Assign a field within that object using its field name Field* x = mt->type->GetField("x"); int* x_ptr = (int*)x->GetPtr(mt); *x_ptr = 3; |

That covers the fundamentals, from which the rest of the code was built upon.

Serialisation

We only supported one form of a serialisation and that was a versionable, binary IFF variant. Serialisation was only ever applied to a memory buffer that grew as more data was added to it. The chunk header was similar to:

struct ChunkHeader { // Hash of the field name to uniquely identify the chunk unsigned int name_hash; // Size of the data unsigned int size; // Type data when the field was serialised unsigned int type_name_hash; unsigned int type_flags; }; |

Unlike IFF, this uses the hash of the field name to uniquely identify a chunk. If the field didn’t exist, the data was skipped during load and not preserved. It also uses 8 bytes to carry a small description of the type of the field when it was serialised. This allowed us to change the type or attributes of a field and have the loading code skip over the data or convert it if any of those changed.

The serialisation logic was very similar to that discussed in part 1 with some additions. Reflectabit’s binary serialisation contains a simpler example of this.

One minor feature was the ability to use masks to specify what fields would be serialised based on what attributes the field had set. This allowed the use of the same code path for serialising files on disk and network messages, described shortly.

As we only supported one file format, custom loading and saving function pointers were attached to each field, keeping everything simple and fast:

typedef void (*LoadFieldFunc)(Buffer& inbuf, unsigned int flags, void* object); typedef void (*SaveFieldFunc)(Buffer& outbuf, unsigned int flags, void* object); struct Field { // additions to Field... Field& LoadSave(LoadFieldFunc load, SaveFieldFunc save) { load_field = load; save_field = save; return *this; } LoadFieldFunc load_field; SaveFieldFunc save_field; }; // An example of texture type registration with custom load/save for the data enum Format { FMT_RGBA, // etc... }; EnumConst format_enums = { EnumConst("FMT_RGBA", FMT_RGBA), }; struct Texture { int width, height; Format format; IDirect3DTexture9* data; }; Field texture_fields = { Field("width", &Texture::width), Field("height", &Texture::height), Field("format", &Texture::format), Field("data", &Texture::data).LoadSave(LoadTextureData, SaveTextureData), }; TypeDB db; db.CreateType<Format>().EnumConstants(format_enums); db.CreateType<Texture>().Base<Object>().Fields(texture_fields); |

The data field above is a raw IDirect3DTexture pointer. A version number was embedded in the field flags, occupying about 5 or 6 bits, I can’t recall which exactly. This allowed the loading code to skip version numbers it didn’t know how to load or, in the case of custom loading code, forward onto the appropriate loading code:

void LoadTextureData2(Buffer& inbuf, unsigned int flags, void* object) { // Given the already known texture dimensions and format (serialised in order) // Create the D3D texture object Texture* texture = (Texture*)object; texture->data = g_Resources->CreateTexture(texture); // Lock the texture, copy the data into it, unlock LockRect r = texture->Lock(); memcpy(r.data, inbuf.MemBuf(), TexSizeBytes(texture)); texture->Unlock(); } void LoadTextureData(Buffer& inbuf, unsigned int flags, void* object) { // Dispatch to the correct loader unsigned int version = GetVersion(flags); switch (version) { case 1: LoadTextureData1(inbuf, flags, object); break; case 2: LoadTextureData2(inbuf, flags, object); break; } } void SaveTextureData2(Buffer& outbuf, unsigned int flags, void* object) { // Lock the texture, read the data from it, unlock Texture* texture = (Texture*)object; LockRect r = texture->Lock(); outbuf.Write(r.data, TexSizeBytes(texture)); texture->Unlock(); } void SaveTextureData(Buffer& outbuf, unsigned int flags, void* object) { // Always save as the latest format SaveTextureData2(outbuf, flags, object); } |

The code above describes the texture loading code in its early state. Eventually, texture streaming was supported; at which point, the texture data was serialised on-demand and the reflection code was merely responsible for creating texture handles.

Unreal performs version upgrades incrementally: it can load old file formats and when you save your package, it will be saved in the new format. Tools can be written which further automate this process. When it comes to serialising complicated data, Unreal’s solution is a single method within your object. Over time you prune old loading code as your compiled data catches up. We found that our modification to this process was more stable and easier to maintain.

Pointers were serialised as the hash of the name of any object being pointed to. Because we didn’t control the order of loading (that was up to Unreal) we had to come up with ways of ensuring pointers to objects that weren’t yet created were satisfied. I think the solution we settled on was to create a proxy object using the type information embedded in the field chunk before actual object creation came along later and completed the creation. While this also handled the issue of circular references, it wasn’t a great solution, but it worked!

After adding support for stream writing containers of PODs as an optimisation, bitfields and automatic endianness swapping, the serialisation didn’t change much and was a pretty straight-forward piece of code.

The Network Server

The engine had the ability to accept arbitrary TCP/IP connections while running on Windows or console, using Winsock. Again, the code was pretty minimal, just a bunch of socket, bind, accept, send, recv calls for dealing with anonymous chunks of data.

The network server ran on the same thread as the engine, polling once a frame for any incoming connections or data. Obviously you don’t want to do this kind of thing for actual game network code but for development code it works superbly – don’t let any work-hungry programmers try to convince you otherwise.

There was only one format of network message it could send and receive, but those messages were of arbitrary length and contained reflection-serialised data within them:

struct MessageHeader { unsigned int type_name_hash; unsigned int object_name_hash; unsigned int message_size; }; |

There were two ways the network server could respond based on the contents of the Message type:

- The network server had an internal map of event type names to handler functions. If the message type name matched anything in that map, the message data would be deserialised and passed onto the handler function.

- Failing that, the message would be interpreted as a full or partial object replication request. The message data would be deserialised and assigned to the requested object.

This was enough to allow tools written in C# to remotely interact with the game through a network socket, with the appropriate network and marshalling code written on the C# side:

bool NetworkServer::ReceiveNextMessage() { // Receive an entire message header before proceeding or leave if there are no more messages MessageHeader header; if (!m_Network->Receive(&header, sizeof(header))) return false; // Read the message data into a memory buffer Buffer data(header.message_size); m_Network->Receive(data.MemBuf(), header.message_size); // Get the message type, skipping the data if it can't be handled Type* message_type = m_TypeDB->GetType(header.type_name_hash); if (message_type == 0) return true; // Is this an event being sent remotely? if (Event* event = m_Events.find(header.type_name_hash)) { // Create an object of the event type and parse its data Object* object = m_ResourceDB->CreateObject(header.type_name_hash); SerialiseLoadBinary(data, object); // Dispatch to the handler and destroy the message object event->handler(object); m_ResourceDB->DestroyObject(object); return true; } // This is an object replication request; need to get the object and serialise all or only // a few of its fields - at least, only those that are specified due to the binary IFF nature // of the serialisation code. Object* object = m_ResourceDB->GetObject(header.object_name_hash); if (object) SerialiseLoadBinary(data, object); return true; } |

The network server could similarly send events and replication requests to remote machines if it needed to.

C# Tools Development

Regardless of your wrapper of choice, developing tools in C/C++ can be quite painful. Microsoft managed to hit a sweet spot with with C#, .NET and Forms development that was very easy to use and not interminably slow and bloated. However, it did require the use of 3rd party libraries to get some truly useful/fast user interfaces to replace stuff like the woeful grid control. We used it to good effect, developing a few tools in C# that would communicate directly with the running game on either Windows or the console, such as:

- A material editor.

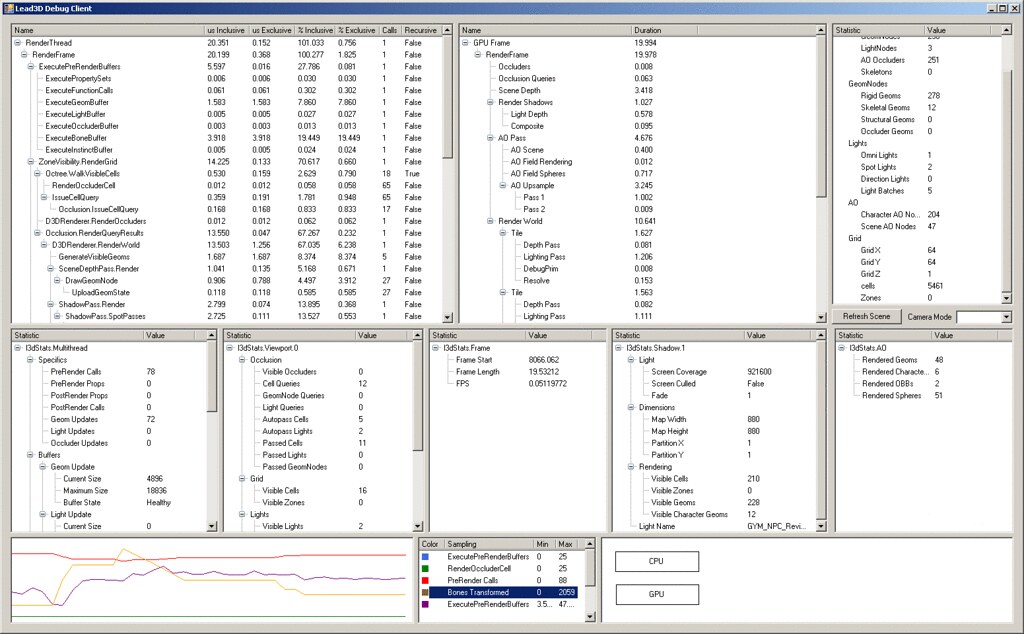

- A sort-of “realtime PIX” profiling and debugging tool.

- A post-processing editor.

These were all small applications that existed outside the UnrealEd framework that, once launched, could connect to any running game and manipulate/read its state.

The profiling tool is one example I can share. In “real-time” (every couple of ms), it updated all of its panels with performance info on the GPU and CPU – much of the information that PIX was providing back in 2006:

The programmers and level designers could use this (along with other methods) to quickly diagnose problems in any levels they were constructing. There is a higher resolution version on Flickr, here.

In order to achieve this, we needed a set of C# libraries that understood the C++ reflection API, its serialisation and its object model. Network communication was trivial and much easier than using Winsock on the C++ side – we just used System.Net.Sockets to build the C# equivalent of the C++ NetworkServer.

The C# clients and the C++ network server would communicate with messages that would be serialised either end. The steps involved in getting messages from C# to C++ were:

- All messages and their parameters were defined in C#.

- A separate C# tool would use System.Reflection to walk the message types and automatically generate C++ code with the equivalent message structures, alongside their C++ reflection registration code.

- At runtime, marshalling code would use System.Reflection to create messages of the requested type and serialise their parameters into an intermediate runtime object model.

- The intermediate representation would then be serialised to a byte stream that the C++ code could load (we only used the binary serialisation discussed above) and sent over the network.

- The NetworkServer code would pick up the message and use the C++ reflection to create the message object and deserialise its contents.

- Several message handlers attached to NetworkServer would pick up and respond to the messages using the message structures already defined.

While this covers how the two programs logically interacted with each other, it doesn’t explain how the C# tools could modify any object running live in the game. Whenever a C# tool connected to the game, one of the first messages it would send would be a request for the entire C++ type database. Once received, it could use that type information to auto-generate user interfaces, swapping in whatever widget was necessary for the type being edited (e.g. an HSB colour selector, slider, check-box for bools, list-box for enum lookup) and adding tool-tips/descriptions from the C++ metadata.

This was a very stable means of getting type descriptions, as the editor could never be out-of-sync with the game it was editing. Contrast this to methods that involve loading a description of types from a separate file that must be integrated with your build system, somehow.

After that the C# tool would request a copy of all objects currently live in the game. This is where the intermediate object model comes into play. The C# type description API would look something like:

// Equivalent to C++ Name using a C# port of CRC32 public class Name { public string text; public uint hash; } // A minimal copy of the C++ Type structure public class Type { public Name name; public List<Field> fields; public List<EnumConst> enum_constants; } // Just enough information to control marshalling/serialisation and UI generation public class Field { public Name name; public Type type; public string display_name; public string description; public string group; } public class EnumConst { public Name name; public int value; } |

Each allocated C++ object would have an equivalent C# object of the type:

public class Object { Name name; Value value; } |

There would also be a big map of names to allocated C# objects, so whenever a message came through that referenced an object, that object could be retrieved. The intermediate object model was thus:

// Base value object with the type its paired to public class Value { Type type; } // Objects for each type of value representable in C++ public class StringValue : Value { public string data; } public class IntValue : Value { public int value; } public class UIntValue : Value{ // ... public class FloatValue : Value{ // ... // ... // A enum constant where its data is the enum value (can be paired with EnumConst above to get descriptive value) public class EnumConstValue : Value { public int data; } // Pointers could be network-serialised and represented in the tools, also. // They were just names, after-all, and the type could be used to ensure you couldn't point to objects of an incorrect type. public class PointerValue : Value { public Name name; } // Each C++ container had a C# equivalent - the C# equivalent stored Value's public class ArrayValue : Value { public ArrayList data; } public ClassValue : Value { public Dictionary<Name, Value> values; } |

Each Value implementation had various functions for displaying the type at runtime, generating widget controls, serialising and marshalling (converting between C# native and the object model) their contents.

Once you wrote your code for displaying/editing the objects, entire objects could be replicated or the same code could be used to partially replicate an object. The C++ code would simply locate the existing object by name and overwrite only the fields which were present in the network-serialised data. The editor tools could request that the runtime generate data for it; the material editor, for example, would request material, mesh and texture thumbnails be generated and sent over the network on demand.

And finally, on Windows, the C# tools could create a blank canvas window, send its HWND over the network and the 3D renderer would happily render into it, taking cues from whatever keyboard and mouse input was sent along with it. This meant that we didn’t need to send over any of the heavyweight data, such as textures or vertices, choosing instead to give them the “network transient” attribute. Of course, that information could be sent over on-demand (for when you wanted to inspect all pixels of a texture, for example) but it was never stored persistently.

This method of tools development was really quite natural: you could iterate amazingly quickly on the C# tools code while the game was still running, edit your C# code, build (a couple of seconds), and have it running and connected another couple of seconds later without any expensive level/data reloads!

Conclusion

The methods contained within are among those that you should keep in your bag of tricks and bring out when you need good, scalable solutions quickly. If you’re into the new-fangled idea of developing your tools in a web browser, these techniques will get you most of the way there and even allow you to write native browser games without having to write plugins!

If you’re meta-programming hungry, part 3 will cover some more elaborate reflection technology which I wouldn’t necessarily recommend these days. It will hopefully serve as a lesson in how things can get complicated very fast. Stay tuned, as the internals of a basic IDL compiler will also be covered.